Probability. Quantum mechanics loves it. Perhaps this love of the uncertain or the unknown is epitomised by no less than the man, the myth, the rejector of all previously known logic: Erwin Schrödinger.

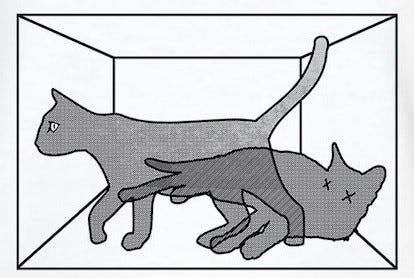

Imagine the following situation: Mr. Schrödinger places a hypothetical cat in a hypothetical box with a hypothetical vial of poison gas attached to a hypothetical Geiger counter (a radiation detector) placed next to a hypothetical radioactive atom that is left to hypothetically decay for an hour in that hypothetical world. It’s all very hypothetical. Josh and James would be proud.1 Anyway, if the atom decays, then the Geiger counter panics, breaks the vial and voila: the cat is dead. If it doesn’t, then the cat just gets bored.

To anybody but Mr. Schrödinger (and other quantum theorists of the time), the existence of this hypothetical cat and thought experiment is either of no concern or a cause of visceral hatred. Indeed, even Stephen Hawking commented ‘When I hear about Schrodinger's cat, I reach for my gun.’2 However, to Mr. Schrödinger, its existence is perhaps worthy of existential questioning, as we will later discover.

Okay, story time’s over; I promise there’s meaning in all this madness. The legend of Schrödinger’s cat raises questions about all aspects of quantum mechanics in defining our reality (if it does define any conceivable reality at all). Schrödinger not only questions the effectiveness of quantum theory itself but also scrutinises classical physics and its limitations on our everyday perception of the world.

In hopes of avoiding further reader confusion, I will analyse only the Copenhagen interpretation, but feel free to step foot in the rabbit holes of others; perhaps you’ll find the Many Worlds Interpretation, Objective Collapse theory, or even the de Broglie-Bohm interpretation intriguing (although keep in mind that the quantum world is paradoxical at times, and I cannot accept responsibility for any cases of insanity beyond this post…)

But I digress. To Copenhagen…

The Copenhagen Interpretation

So you’ve made it this far. You probably want to know what the Copenhagen interpretation is and what exactly it states. Good question. I will admit, it’s a bit wishy-washy…

More than merely an interpretation of Schrodinger’s cat and its unfortunate end, the Copenhagen interpretation was the first interpretation of quantum physics as a whole, coined by Niels Bohr and Warner Heisenberg (as well as Max Born and several other names utterly irrelevant to the point of this article that I shall, therefore, not list). 3

One key aspect of said interpretation is quantum indeterminacy, which one must understand before examining the interpretation itself. Consider this definition by Andrew Jones for ThoughtCo:

‘The quantum wave function portrays all physical quantities as a series of quantum states along with a probability of a system being in a given state. Consider a single radioactive atom with a half-life of one hour.

According to the quantum physics wave function, after one hour the radioactive atom will be in a state where it is both decayed and not decayed. Once a measurement of the atom is made, the wave function will collapse into one state, but until then, it will remain as a superposition of the two quantum states.’

Circling back to Schrodinger’s cat, we can apply a similar logic:

The cat is simultaneously alive and dead.

It is here and now, dear reader, that I recommend that you abandon any previous preconceptions of reality. Done? Great. Moving on…

[continued] …‘The Copenhagen interpretation states that the act of measuring something causes the quantum wave function to collapse. In this analogy, really, the act of measurement takes place by the Geiger counter.

…Whether or not the scientist opens the box is irrelevant, the cat is either alive or dead, not a superposition of the two states.’ 4

However, a more philosophical Copenhagen-esque approach may suggest that, when observing quantum phenomena, we - as conscious beings - force it to meld itself to our classical preconceptions (thanks, Newton), thus ‘collapsing’ the quantum world of probability, paradox and superposition into something much, much inferior so that we mere humans can comprehend it.

‘So don’t ask who killed Schrodinger’s cat - you did.’

~ Jan Westerhoff

[above]5

Well, that’s all for today.

Wie üblich, feel free to peruse the buttons below, and thank you very much for taking the time to read this - it means a lot.

A brief reference to comedians Josh Widdicombe and James Acaster from Hypothetical (a TV show on a channel called Dave). It was just too fitting not to include.

Westerhoff, Jan. ‘The quantum world.’ New Scientist Essential Guide | The Nature of Reality, edited by Richard Webb, New Scientist, 2020, p. 67.