So… I think it’s fair to say I have somewhat of an apology to make. Recently I’ve been sticking my fingers in a few too many pies and - to continue the metaphor - this one’s been left to get stale at the back of the cupboard. But I’m back now - and intend to linger more consistently over the next few weeks…

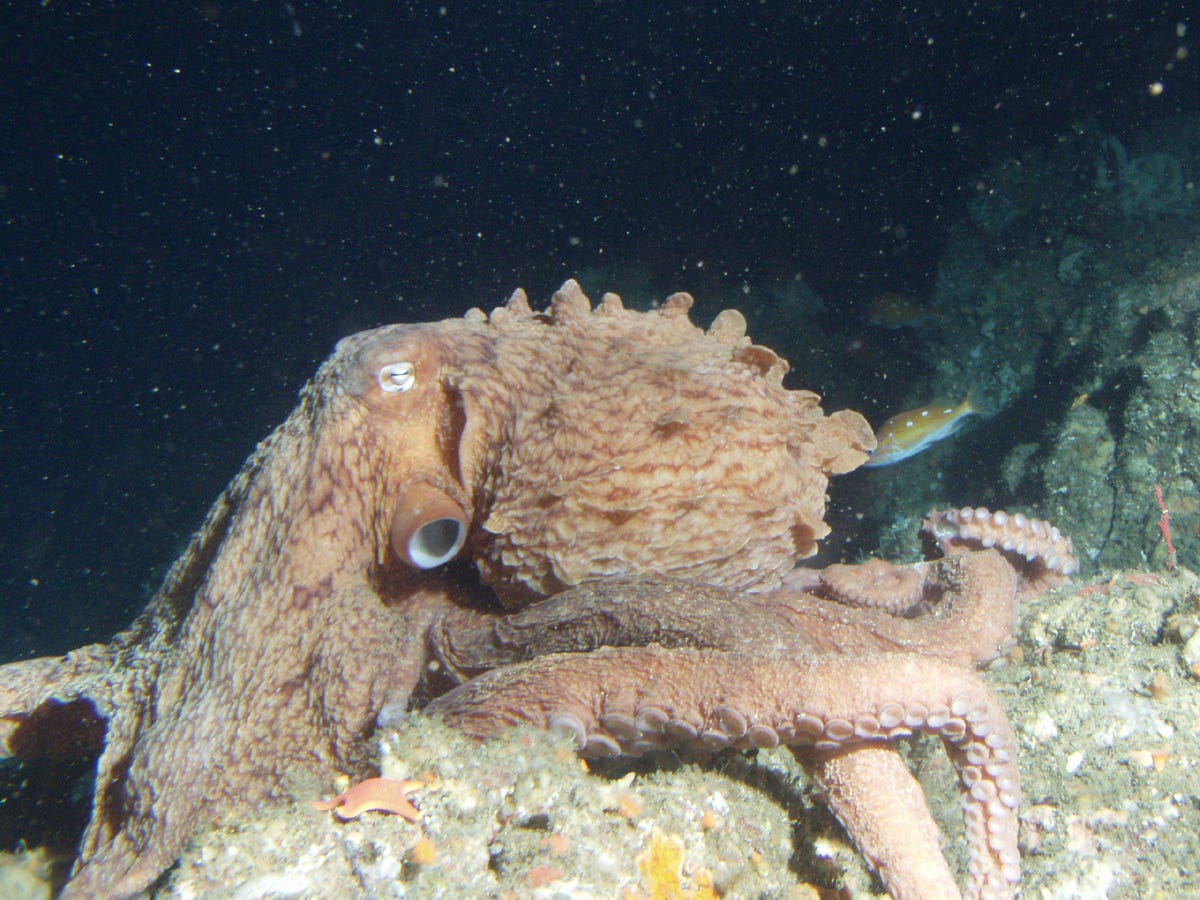

Often misunderstood as a simple sea monster or a mere curiosity of nature, the octopus is, in fact, one of the most intelligent, versatile, and mysterious beings on the planet. And yes, the entire point of this article is for me to nerd out to my heart's content until you fully agree with the above statement. I do not apologise.

Octopuses are soft-bodied, eight-limbed molluscs belonging to the order Octopoda. They’re part of the class Cephalopoda, including squids, cuttlefish, and nautiluses. There are over 300 species of octopuses, ranging in size from the tiny Octopus wolfi, which measures just over an inch, to the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dolfeini), which can span up to 16 feet and weigh more than 150 pounds.

The most common octopus however, is the Octopus vulgaris and for simplicity’s sake I shall simply be referring to it as “octopus” throughout the rest of this rather glorified factfile…

And that’s enough Latin for one day.

Anyway, octopi are known for their bulbous heads, large eyes, and most notably, their eight “arms” (not tentacles!!!!!!!!!!!!!) - well technically 6 arms and 2 legs according to some marine biologists - each lined with suckers that can grasp, see, and even taste. The octopus’ body is highly flexible, lacking any bones, which allows it to squeeze through incredibly narrow openings. Houdini could never.

And here I shall insert a random compilation of some of my favourite octopus facts:

One of the most striking features of octopuses is their ability to change colour and texture almost instantaneously. This is made possible by specialized skin cells called chromatophores, iridophores, and leucophores. Chromatophores contain pigments that can expand or contract to alter the colour of the octopus’ skin, allowing it to blend seamlessly with its surroundings. Iridophores and leucophores reflect light, helping the octopus achieve even more complex patterns and hues. This camouflage ability is not only used for hiding from predators but also for communicating with other octopuses, making it a vital tool for survival and a flexible fashion sense.

When threatened, they can eject a cloud of ink, which acts as a smokescreen, allowing them to escape from predators. This ink also contains substances that can dull the predator’s sense of smell, further aiding in the octopus’ getaway.

Some species of octopus can detach an arm when caught, which continues to writhe and distract the predator as the octopus escapes—a process known as autotomy.

Unlike humans and many other animals, octopuses have a decentralized nervous system. This means that while they have a central (doughnut-shaped, in other words: torus) brain located between their eyes and surrounding their oesophagus, a large portion of their neurons are distributed throughout their arms (up to two-thirds of them). This unique nervous system allows each arm to operate somewhat independently, making decisions and performing tasks without direct input from the “brain”.

Another intriguing aspect of octopus anatomy is their beak, the only hard part of their body. Located at the centre point where their arms converge, the beak is used to crush and consume prey, such as crabs and molluscs. The beak is so powerful that it can break through shells, allowing the octopus to access the soft flesh inside.

Octopodes possess three hearts. Honestly, how cool is that? Two of these hearts pump blood through the gills, while the third pumps it to the rest of the body. Their blood is copper-based (hemocyanin), rather than iron-based like ours (haemoglobin), which is more efficient at transporting oxygen in cold and low-oxygen environments, such as the deep sea.

Moving on…

One of the most compelling reasons as to why octopuses have captured human interest is their extraordinary intelligence. Despite being invertebrates, octopodes exhibit behaviours that are considered signs of high cognitive functioning, such as problem-solving, memory, and even play. As well as a respectable amount of antisocial behaviour.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the octopus’ ability to solve complex puzzles, navigate mazes, and remember solutions to problems over time. For example, octopuses have been observed opening jars to access the food inside—an impressive feat given the coordination and understanding required to do so. They can also distinguish between different shapes and patterns, showing a level of visual processing that rivals that of some mammals.

I would highly recommend watching the video below should you have the time.

Octopuses are also known for their curiosity and playfulness (as above). In captivity, they have been observed playing with objects such as toys, shells, and even water streams (again, you might want to watch the video…). This behaviour is particularly intriguing because play is generally considered a sign of higher intelligence, seen primarily in animals with complex social structures. The fact that octopuses, typically solitary creatures, engage in play suggests that their cognitive abilities are highly advanced.

Another remarkable aspect of octopus intelligence is their use of tools. Some species, like the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus; okay, I’m sorry… no more Latin after this - promise), have been observed collecting coconut shells and using them as shelters—a behaviour that was once thought to be unique to humans and certain primates.

Communication among octopuses is also complex and varied. While they do not have vocal cords, they can communicate through body language, changing colours, and even postures. During mating, for example, octopi will use specific colour patterns to signal readiness or to ward off rivals. This form of communication, combined with their ability to mimic other creatures and objects, makes octopodes masters of deception and disguise.

Indeed, the reproductive strategies of octopuses are about as curious as the creatures themselves.

Reader discretion is advised. If this discussion is simply too intimate, please skip to after the italics.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t get David Attenborough to voice this part, so you’ll have to use your imagination..

Mating is often a risky endeavour, especially for the smaller male, who must approach the larger female cautiously to avoid being eaten. The male octopus uses a specialized arm called the hectocotylus (okay, fine, I broke the promise I’m sorry) to transfer spermatophores (packets of sperm) to the female’s mantle cavity. After mating, the female lays thousands of eggs, which she meticulously cares for until they hatch.

During the incubation period, which can last several months, the female octopus often stops eating and dedicates all her energy to protecting and oxygenating her eggs. This level of parental investment is extraordinary in the animal kingdom. However, it comes at a great cost—the female usually dies shortly after the eggs hatch, having expended all her resources.

And so the young octopuses, or hatchlings, are left to fend for themselves from the moment they emerge. They start their lives as tiny planktonic creatures, drifting with the currents and feeding on small prey. As they grow, they gradually descend to the ocean floor, where they begin their solitary lives as adults.

The lifespan of an octopus is relatively short, unfortunately, typically ranging from six months to a few years, depending on the species. Despite this, their rapid growth and development, combined with their remarkable intelligence, allow them to make the most of their brief existence.

And here comes the sad bit…

Humans aren’t exactly innocent when it comes to keeping the lifespan of these creatures to a minimum.

Let me show you some search results…

the query: “baby octopus vulgaris” (for context: I was just looking for some cute pics)

Look, I’m not here to bash any meat eaters. All I’m here to say is that it’s sad. It’s sad that it’s considered socially acceptable to eat these creatures. And it doesn’t make any sense - at least to me.

But before I go, just one more thing…

You may be wondering about the title. You may also be wondering about my incosistent use of the plurals of octopus. Well, it turns out they’re all correct (my personal fave being octopodes - any budding etymologists feel free to check out this link here)

Aaaaaand that’s all for today. As always, don’t forget to like, subscribe, and scream about it from the top of mount everest etc. and I shall attempt to return in a reasonably timely manner…

Ooh and do let me know any of your favourite octopus facts in the comments below

3. is so incredible!!! Pleaaaaase could you do one on platypuses/platypodes/platypi? Quaeso? :-)

Great to see you back Rachel and I agree with you that the octopus is an amazing creature that deserves to be protected